Eigen values and vectors

Definition

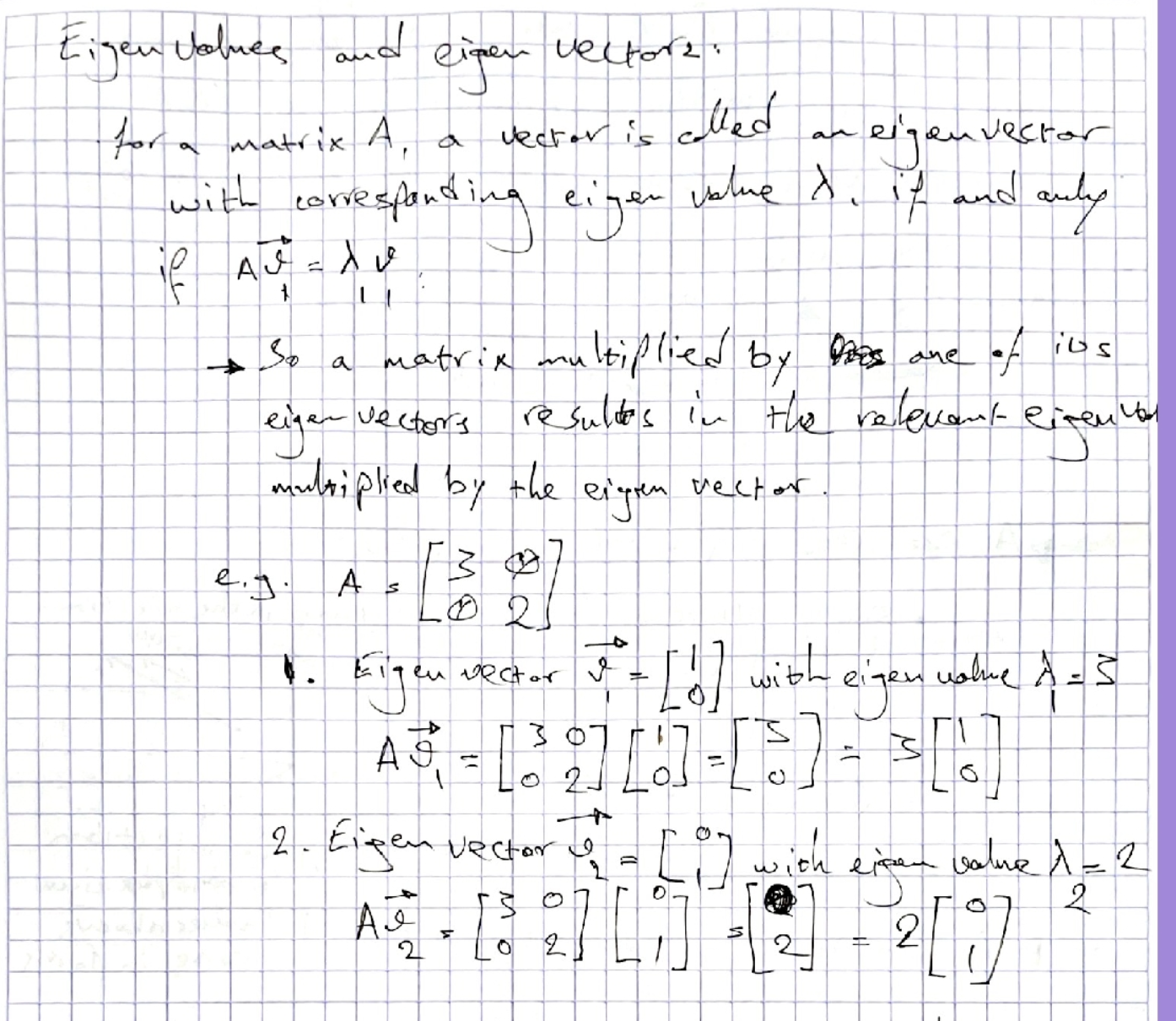

For a square matrix A, a scalar λ is an eigenvalue of A if there exists a non-zero vector v such that:

Av = λv

The non-zero vector v is called an eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue λ.

Geometrically, this means that when A is applied to v, the result is a vector pointing in the same (or opposite) direction as v, but possibly scaled by λ.

Finding Eigenvalues

To find the eigenvalues of a matrix A:

- Write the eigenvalue equation: Av = λv

- Rearrange to: (A - λI)v = 0, where I is the identity matrix

- This system has non-zero solutions v if and only if det(A - λI) = 0

- Solve the characteristic equation: det(A - λI) = 0

- The roots of this equation are the eigenvalues of A

Finding Eigenvectors

For each eigenvalue λ:

- Substitute λ back into (A - λI)v = 0

- Solve this homogeneous system to find the non-zero solutions v

- These solutions form the eigenspace for eigenvalue λ

The dimension of the eigenspace equals the algebraic multiplicity of λ minus its geometric multiplicity (the number of linearly independent eigenvectors corresponding to λ).

Properties of Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

-

Determinant: det(A) equals the product of all eigenvalues (counting multiplicities)

-

Trace: tr(A) (sum of diagonal elements) equals the sum of all eigenvalues

-

Similar matrices: If B = P⁻¹AP, then B has the same eigenvalues as A

-

Matrix powers: If λ is an eigenvalue of A with eigenvector v, then λᵏ is an eigenvalue of Aᵏ with the same eigenvector

-

Matrix functions: If λ is an eigenvalue of A with eigenvector v, then f(λ) is an eigenvalue of f(A) with the same eigenvector

-

Inverse: If λ ≠ 0 is an eigenvalue of A, then 1/λ is an eigenvalue of A⁻¹

-

Transpose: A and A^T have the same eigenvalues

Special Cases

1. Symmetric Matrices

For a symmetric matrix (A = A^T):

- All eigenvalues are real

- Eigenvectors corresponding to distinct eigenvalues are orthogonal

- A complete set of orthogonal eigenvectors always exists

2. Triangular Matrices

For triangular matrices (upper or lower):

- The eigenvalues are exactly the diagonal entries

3. Diagonalizable Matrices

A matrix A is diagonalizable if and only if:

- It has n linearly independent eigenvectors (where n is the dimension)

- Equivalently, the sum of the dimensions of all eigenspaces equals n

If A is diagonalizable, then:

- There exists an invertible matrix P such that P⁻¹AP = D

- D is a diagonal matrix with the eigenvalues on the diagonal

- The columns of P are the eigenvectors of A

4. Complex Eigenvalues

When working in ℝ:

- Complex eigenvalues always appear in conjugate pairs: λ = a + bi and λ* = a - bi

- If v is an eigenvector for λ = a + bi, then v* is an eigenvector for λ* = a - bi

Step-by-Step Calculation Process

Example: 2×2 Matrix

For A = $\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 8 \ 0 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$:

-

Form the characteristic equation: det(A - λI) = det($\begin{bmatrix} 3-λ & 8 \ 0 & 4-λ \end{bmatrix}$) = 0

-

Calculate the determinant: (3-λ)(4-λ) - 8×0 = 0 (3-λ)(4-λ) = 0

-

Solve for λ: λ = 3 or λ = 4

-

Find eigenvectors for λ = 3: (A - 3I)v = $\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 8 \ 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v_1 \ v_2 \end{bmatrix}$ = $\begin{bmatrix} 0 \ 0 \end{bmatrix}$

This gives 8v₂ = 0 and v₂ = 0 With v₂ = 0, v₁ can be any non-zero value Eigenvector: v = $\begin{bmatrix} 1 \ 0 \end{bmatrix}$

-

Find eigenvectors for λ = 4: (A - 4I)v = $\begin{bmatrix} -1 & 8 \ 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v_1 \ v_2 \end{bmatrix}$ = $\begin{bmatrix} 0 \ 0 \end{bmatrix}$

This gives -v₁ + 8v₂ = 0, so v₁ = 8v₂ With v₂ = 1, v₁ = 8 Eigenvector: v = $\begin{bmatrix} 8 \ 1 \end{bmatrix}$

Example: 3×3 Matrix

For A = $\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 \ 0 & 3 & 0 \ 1 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix}$:

-

Form the characteristic equation: det(A - λI) = det($\begin{bmatrix} 1-λ & 0 & 1 \ 0 & 3-λ & 0 \ 1 & 0 & 1-λ \end{bmatrix}$) = 0

-

Calculate the determinant (using cofactor expansion along the second column): (3-λ) × [det($\begin{bmatrix} 1-λ & 1 \ 1 & 1-λ \end{bmatrix}$)] = 0 (3-λ) × [(1-λ)(1-λ) - 1×1] = 0 (3-λ) × [(1-λ)² - 1] = 0

-

Solve for λ: (3-λ) = 0 or (1-λ)² - 1 = 0 λ = 3 or (1-λ)² = 1 λ = 3 or 1-λ = ±1 λ = 3 or λ = 0 or λ = 2

-

Find eigenvectors for each eigenvalue by solving (A - λI)v = 0

Eigenvalue Multiplicities

Algebraic Multiplicity

The power to which (λ - λᵢ) appears in the characteristic polynomial.

Geometric Multiplicity

The dimension of the eigenspace corresponding to λᵢ (i.e., the number of linearly independent eigenvectors).

For a diagonalizable matrix, the algebraic and geometric multiplicities are equal for each eigenvalue.

Diagonalization Process

To diagonalize a matrix A:

- Find all eigenvalues λ₁, λ₂, …, λₙ of A

- For each eigenvalue λᵢ, find a basis for its eigenspace

- Combine these bases to form the columns of matrix P

- The diagonal matrix is D = diag(λ₁, λ₂, …, λₙ)

- Verify that P⁻¹AP = D

A matrix is diagonalizable if and only if it has enough linearly independent eigenvectors to form a basis for the entire space.

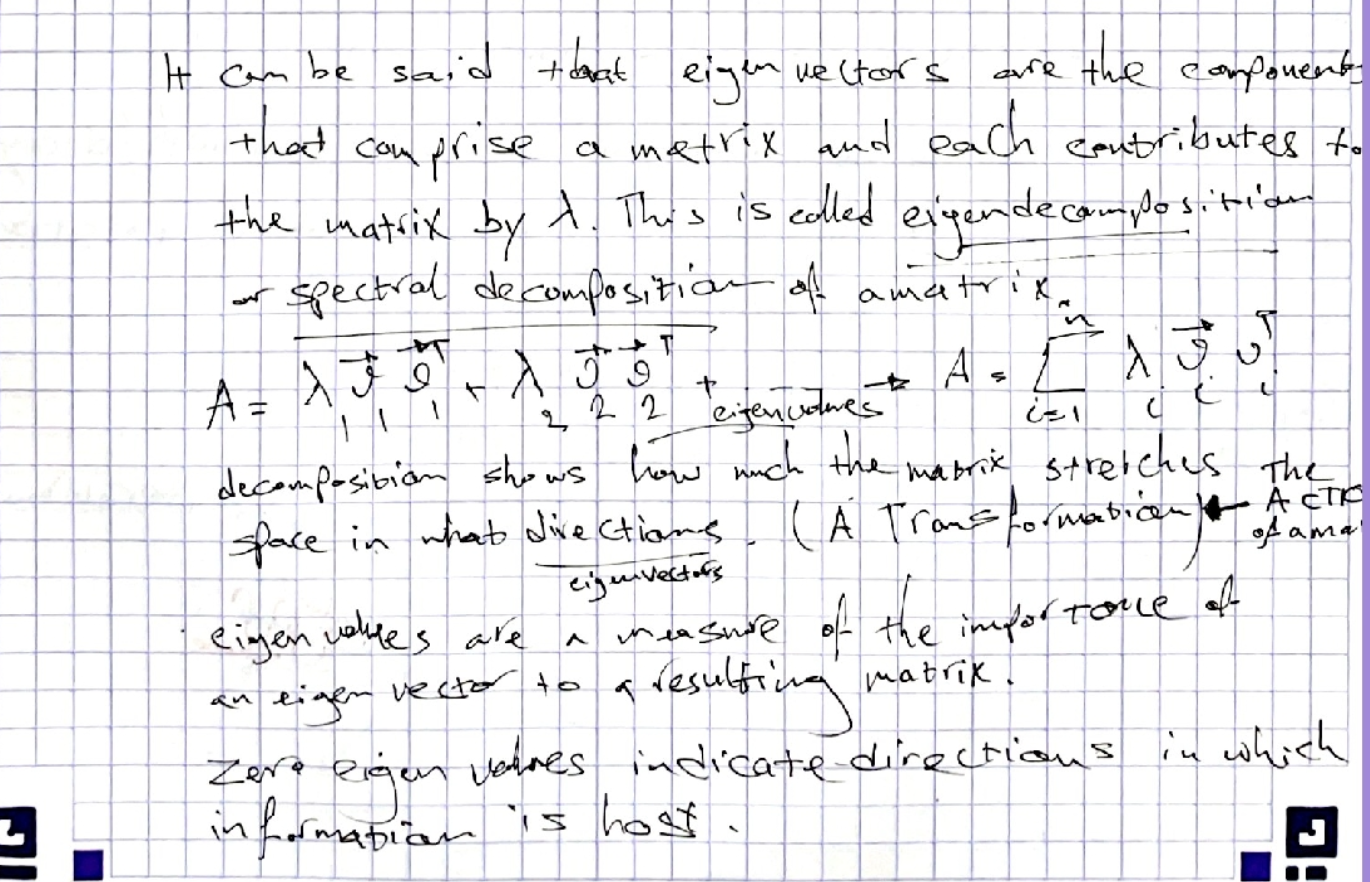

Applications of Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors

- Matrix powers: A^k = PD^kP⁻¹ (where D^k is easy to compute)

- Dynamical systems: Predicting long-term behavior

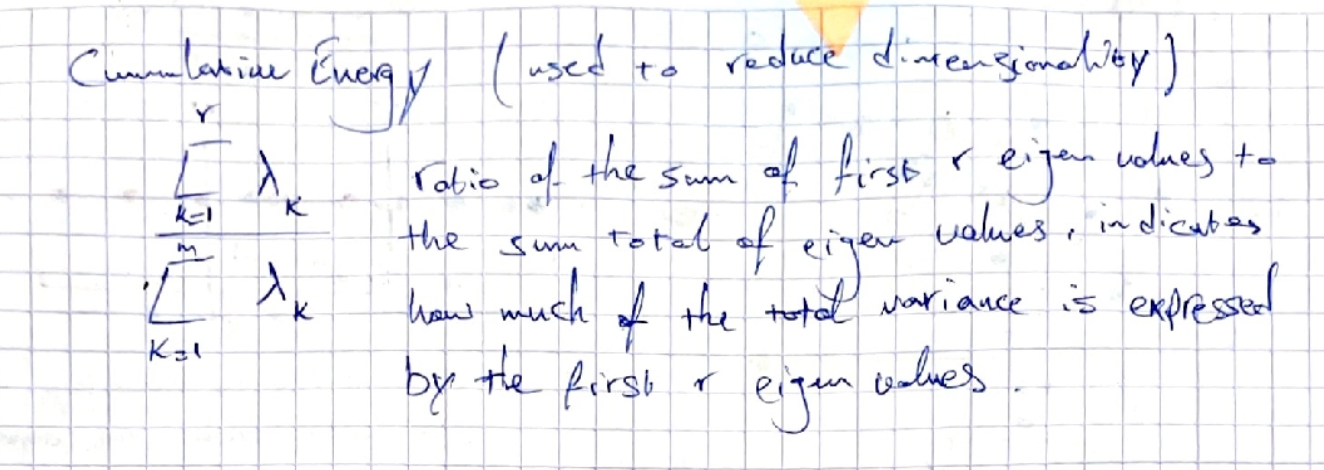

- Principal component analysis: Finding directions of maximum variance

- Differential equations: Solving systems of differential equations

- Markov chains: Finding steady-state distributions

Strategies for Specific Problem Types

1. Finding Eigenvalues of Triangular or Simple Matrices

For triangular matrices, eigenvalues are the diagonal entries.

2. Handling Repeated Eigenvalues

For an eigenvalue λ with algebraic multiplicity m:

- If the geometric multiplicity equals m, proceed normally

- If the geometric multiplicity is less than m, the matrix is not diagonalizable

3. Small Matrices with Simple Patterns

Look for symmetries or special structures:

- Symmetric matrices have real eigenvalues and orthogonal eigenvectors

- Matrices with repeated rows/columns often have 0 as an eigenvalue

4. Computing Matrix Functions

For a diagonalizable matrix A = PDP⁻¹:

- A^k = PD^kP⁻¹

- e^A = Pe^DP⁻¹

- Where e^D = diag(e^λ₁, e^λ₂, …, e^λₙ)

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Forgetting that eigenvectors cannot be the zero vector

- Errors in calculating det(A - λI)

- Not checking for linear independence of eigenvectors

- Confusing algebraic and geometric multiplicities

- Computational errors when finding eigenvectors

Exercise Examples

Example 1: 2×2 Matrix with Complex Eigenvalues

For A = $\begin{bmatrix} 3 & 8 \ 2 & 3 \end{bmatrix}$:

-

Characteristic equation: det(A - λI) = (3-λ)(3-λ) - 8×2 = 0 (3-λ)² - 16 = 0 λ² - 6λ + 9 - 16 = 0 λ² - 6λ - 7 = 0

-

Using the quadratic formula: λ = (6 ± √(36+28))/2 = (6 ± √64)/2 = (6 ± 8)/2 λ₁ = 7, λ₂ = -1

-

Find eigenvectors for each eigenvalue

Example 2: 3×3 Matrix Diagonalization

For A = $\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 1 & 0 \ 0 & 1 & -1 \ 0 & 2 & 4 \end{bmatrix}$:

- Find eigenvalues using det(A - λI) = 0

- For each eigenvalue, find a basis for its eigenspace

- Form the matrix P whose columns are these eigenvectors

- Verify that P⁻¹AP = diag(λ₁, λ₂, λ₃)

See:

Exercises

-

Given the matrix $A = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & -1 \ -1 & -1 \end{pmatrix}$,

(i) for each eigenvalue of $A$, find the corresponding eigenspace;

(ii) find, if there exist, a diagonal matrix $D$ and an invertible matrix $C$ such that $C^{-1}AC = D$;

(iii) check that $C^{-1}AC = D$.

-

Determine the eigenvalues of $A$ in $\mathbb{R}$ where $A = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 8 \ 0 & 4 \end{pmatrix}$

-

Determine the eigenvalues of $A$ in $\mathbb{R}$ where $A = \begin{pmatrix} 3 & 8 \ 0 & 4 \end{pmatrix}$

-

Find the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the following linear transformations:

- $f: \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2$ where $f(x, y) = (2x + 9y, x + 2y)$

- $f: \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R}^3$ where $f(x, y, z) = (4x - y - 2z, 2x + y - 2z, x - y + z)$